The debate is not simply about submarines and missiles. It touches almost every anxiety about the identity of the United Kingdom. The decision may tell us what kind of country – or countries – we will become

by Ian Jack via The Guardian

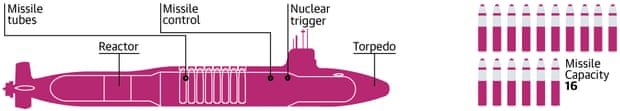

At this moment, a British submarine armed with nuclear missiles is somewhere at sea, ready to retaliate if the United Kingdom comes under nuclear assault from an enemy. The boat – which is how the Royal Navy likes to talk about submarines – is one of four in the Vanguard class: it might be Vengeance or Victorious or Vigilant but not Vanguard herself, which is presently docked in Devonport for a four-year-long refit. The Vanguards are defined as ballistic missile submarines or SSBNs, an initialism that means they are doubly nuclear. Powered by steam generated by nuclear reactors, they carry ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads.

The location of the submarine – both as I write and you, the reader, read – is one of several unknowns. Somewhere in the North Atlantic or the Arctic would have been a reasonable guess when the Soviet Union was the enemy, but today nobody could be confident of naming even those large neighbourhoods. Another unknown is the number of missiles and warheads on board. Each submarine has the capacity to carry 16 missiles, each of them armed with as many as 12 independently targetable warheads; but those numbers started to shrink in the 1990s, and today’s upper limit is eight missiles and 40 warheads per submarine. Even so, those 40 warheads contain 266 times the destructive power of the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

Vickers (now BAE Systems) built the submarine hulls at Barrow; Rolls-Royce made the reactors in Derby; the Atomic Weapons Establishment produces the warheads at Aldermaston and Burghfield in Berkshire. All these inputs are more or less British (less in the case of the Atomic Weapons Establishment, which is run by a consortium of two American companies and Serco), but the missile that they were built to serve and without which they would not exist is American: the Trident D5 or Trident II, also deployed by the US navy, comes out of the Lockheed Martin Space Systems factory in Sunnyvale, California.

According to the Ministry of Defence, a British ballistic missile submarine has been patrolling the oceans prepared to do its worst at every minute of every day since 14 June 1969, when the responsibility for Britain’s strategic nuclear weapons passed from the Royal Air Force to the Royal Navy. Over the course of 46 years, many things have changed. Resolution-class submarines with Polaris missiles were replaced with Vanguards and Tridents nearly 20 years ago. The submarines are far bigger – a Vanguard submarine is twice as long as a jumbo jet – while the missiles have enormously increased their range and the warheads their precision. But the system, known as continuous-at-sea-deterrence or CASD, is essentially the same: four submarines work a rota which has one submarine on a three-month-long patrol, another undergoing refit or repair, a third on exercises, and a fourth preparing to relieve the first. The navy’s code name is Operation Relentless.

This is an epic vigil, born in the cold war and not abandoned by its passing, and the government intends that it continues into a third generation of ballistic missile submarines – the provisionally-named Successor class – that will work to the same pattern as the Vanguards and carry a new version of the Trident D5, now under development. In the end, a military strategy devised to deter attack by the Soviet Union will have outlived its original enemy by at least half a century.

Since the advent of the industrial revolution, few weapons systems have survived so long. The modern battleship, devised under the empty blue skies of Edwardian Britain, demonstrated its vulnerability to air attack even before Pearl Harbor; its useful career lasted hardly 40 years. Britain’s submarine-launched nuclear weapon, on the other hand, seems immune to obsolescence – as well as to financial, social and political hazards such as reductions in public spending, deindustrialisation, and the growing possibility of the break-up of the kingdom it was designed to protect.

2. ‘This project is a monster’

The Scottish Question is a familiar one. But Trident sits at the heart of a more complicated puzzle – what we might call the British Question – and embodies many of the crises and anxieties that have afflicted the United Kingdom since the second world war: the passing of empire, the “special relationship†with the United States, the decline of manufacturing and the disappearance of an industrial working class (and its consequences for the Labour party) – and, of course, the spectre of Scottish independence and the end of a United Kingdom. Trident and its ancestors have been among the causes and consequences of all of them. Where and how (if at all) its successors are deployed will be a measure of the kind of country, or countries, that Britain becomes.

The Strategic Defence and Security Review that was presented to parliament last November described the building of the four Successor submarines as “a national endeavour … one of the largest government investment programmes, equivalent in scale to Crossrail or High Speed 2â€. It will “require sustained long-term effortâ€, the report added, along with radical organisational and managerial changes to “create a world-class, enduring submarine enterpriseâ€. The boosterism that inflects this language may reveal rather than disguise an underlying nervousness: the more a British government talks of “world-class†schemes and institutions, the faster we should count the spoons.

Crossrail and HS2 are Britain’s most expensive public infrastructure projects (with the possible exception of the Hinkley Point nuclear power station, whose eventual cost to the public purse is hard to quantify). Recent estimates put the cost of Crossrail at £15.9bn and the first leg of HS2 – the 120 miles between London and Birmingham – at £30bn. The defence review increased the estimated manufacturing cost of the four Successor submarines to £31bn from an estimated £25bn that had held good from five years before, and for the first time added a contingency estimate of another £10bn.

Delivery of the new fleet, already delayed from the early 2020s to 2028, is now scheduled to begin in the early 2030s, postponing the withdrawal of Vanguard submarines at least 10 years beyond their expected operational life. According to the defence review, the increased cost and delayed schedule “reflect the greater understanding we now have about the detailed design of the submarines and their manufactureâ€. Beyond this opaque statement, the Ministry of Defence will not explain why the cost should have risen by nearly a quarter during five years of near-to-zero inflation, for a programme that was authorised (by Tony Blair’s government) as long ago as December 2006 and which has already cost £3.9bn in its so‑called design phase. And this is only the beginning of mountainous public expense.

Until last autumn, the generally accepted figure for the price of the entire Successor programme – and the one used by its critics, such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – was £100bn. This is the cost of building and then arming, running and repairing four nuclear submarines over 40 years of operational life, followed by their upkeep as decommissioned hulks until the navy decides how to dispose of them. (A safe way of scrapping a nuclear submarine has still to be found; the 19 that the Royal Navy has so far withdrawn from service – the oldest of them in the 1980s – are all still laid up in navy dockyards at Rosyth and Devonport.)

But in October, the Tory MP Crispin Blunt, a Trident sceptic, used information contained in a parliamentary reply from a junior defence minister, Philip Dunne, to estimate a far higher figure. Dunne had said that the in-service cost of the Successor programme would be about 6% of the annual defence budget over the project’s lifetime. Nobody, of course, can know what the UK’s defence budget will be in 20 years’ time; Blunt’s calculations presumed that it would not fall below 2% of GDP, which is the present government’s promise, and that GDP would grow at the rate expected by the government and the International Monetary Fund. On that basis, and on the assumption that in-service costs would run from 2028 to 2060, Blunt concluded that Successor would cost £167bn – a price, he said, that would consume double its predecessor’s proportion of the defence budget and was now “too high to be rational or sensibleâ€.

It may turn out to be lower. The new submarines may not last so long in service as the 32 years assumed by Blunt, and the principle of continuous-at-sea-deterrence could be modified – continuous only at times of international tension, for example – or even abolished by a future government. On the other hand, the cost could be higher. Dunne’s figure for the submarines’ building costs – £25bn – was raised by at least £6bn only a month later. Appearing in October before parliament’s public accounts committee, the senior civil servant at the Ministry of Defence, Jon Thompson, could only say that it was “extremely difficult†to estimate future costs – calling it “the project that most keeps me awake at night†and “a monsterâ€. Stewart Hosie, the Scottish National party’s deputy leader at Westminster, said it was “truly an unthinkable and indefensible sum of money to spend on the renewal of an unwanted and unusable nuclear weapons systemâ€.

After independence itself, the SNP’s best-known political aim is the ejection of the UK’s nuclear-missile fleet from its base at Faslane on the Clyde. Over the next 15 years, a second referendum on the independence question in which Scotland votes to leave the United Kingdom is at least a strong possibility. The SNP, should it form the first independent Scottish government, would no doubt be pragmatic and opportunistic in its negotiations with London, but it seems unlikely that Faslane would continue as the home of another state’s nuclear deterrent. Its place in the SNP’s rhetoric has become far too prominent for that kind of compromise, even if London wants it.

So far all the Ministry of Defence will say is that there are no plans to move the nuclear deterrent from the Clyde and that “any alternative solution would come at huge and unnecessary costâ€. But unless the Trident renewal programme is something that the government secretly wants to cancel and would be happy to see sunk by Scottish independence, plans must exist to move the base out of Scotland. “Huge and unnecessary cost†– so far unspecified but certain to be several billion – is therefore what the UK-minus-Scotland will face.

3. The landscape of the cold war

Faslane, officially Her Majesty’s Naval Base Clyde, is one of the most unexpected sights in modern Britain. The visitor imagines a small dockyard disfiguring a bare Scottish coast. What he finds instead is a long settlement that stretches for nearly two miles down the eastern shore of the Gareloch, the gentlest and most suburban of the Clyde’s seven larger sea lochs, an hour’s journey from Glasgow by commuter train and local bus.